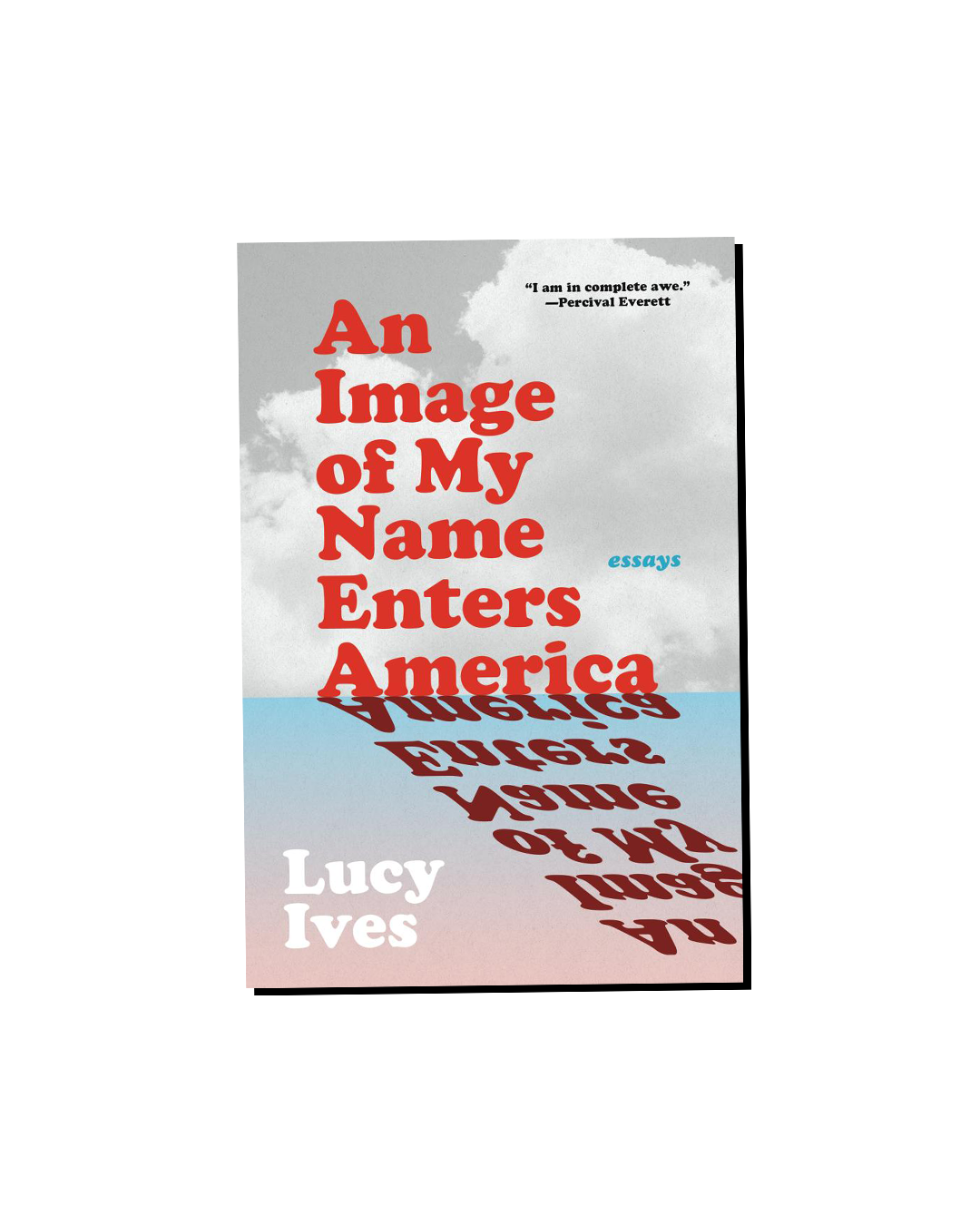

The Ends of Innocence: On Lucy Ives's “An Image of My Name Enters America”

Lucy Ives | An Image of My Name Enters America: Essays | Graywolf Press | October 2024 | 336 pages

During my junior year of college, I lived in a house full of ambitious young men. We were not Econ majors, however. Not doctors nor lawyers nor titans of industry in training. We were artists and writers and musicians and intellectuals. We spent a lot of time at used book and record stores. One of us carried a copy of Derrida’s Of Grammatology around like a bible. You get the idea. These were the years of Y2K rapture-tripping, before 9/11 shattered the world—the forecasted apocalypse that never came to pass, as opposed to the actual one we didn’t see coming. I want to say that these were innocent years, that there was an innocence to proto-internet life. For it has often felt like the world in which I went to college is not the world I’ve lived in ever since.

“The gulf between the world of the young and the world of the old,” writes Lucy Ives in her new essay collection, An Image of My Name Enters America, “rises uncannily out of the floor. It can be perceived.” In a sense, this is the book’s thesis, the organizing principle that guides her explorations. From a young age, playing with My Little Ponies—or, better yet, watching them on TV—she strives not to “become old and stiff and cruel,” not to forget that she is living. For Ives, a My Little Pony doll is not simply a toy, much less “an unnatural fetish” or a “plasticky, pastel” symptom of an attenuating culture. It is a technology, a translating device, a portal. “Remain vulnerable,” the unicorn reminds her, even as the gulf between child- and adult-hood gapes wider. It may be that Ives means, in assembling these essays, to remind us too.

What’s remarkable about Ives’s collection is not so much that she draws attention to that evergreen dilemma, but that for a certain kind of (formerly) ambitious literary young person, educated at a certain kind of elite-ish institution, Ives has written perhaps the keenest retrospective of those years just before and just after the new millennium. More to the point, Ives demonstrates how our sliver of Gen X straddles two major epochs, and how, as a result, we are subject to two distinct sets of historical forces. “Funny,” she writes, “how access to scads of information has made many of us wish to be trapped in another moment in which what can be known by a human is far more limited.” Ives, like myself, came of age in that prelapsarian moment, when if you wanted to drive to California from Michigan, as I did in the summer of 2001, you either had to look up the route in an atlas or print out a bundle of Mapquest pages – neither would tell you what you’d be missing by crossing southern Utah at night. For us, the gulf between young and old is also the gulf between absolute glut and its now-unimaginable absence. “It is very weird,” she writes, “that major events in my immediate family history remained obscure for over thirty years of my life—but that I had only to enter three words into Google to watch a veil fall.” Forgive us our innocence: we remember a time when we were.

The five essays contained in An Image of My Name Enters America could be said to obsess over that innocence, tracking it across a wide range of subjects–from childbirth to pop culture to literary theory, and from medieval tapestries to family history to science fiction. Celine Nguyen, writing in The Believer, provides a handy thumbnail catalog; she also perceptively observes Ives’s talent for mixing high and low culture in a way that’s neither didactic nor glib. Indeed, the essays amble through their subjects in a loosely braided form that will be familiar to readers of nonfiction. The outlier, formally speaking, is the fourth essay, a sweeping tour de force entitled “The End.” Written as an abecedarian (26 sections corresponding to the letters of the alphabet), “The End” takes it cue from (and perhaps winks at) Edward Said, whose “Abecedarium Culturae: Structuralism, Absence, Writing” (1971) offered an early critique of deconstructionist thought. But it’s the collection’s efforts, throughout, to reckon with an earlier self that will be more resonant with most readers. “[W]hat a strange girl I am,” Ives writes, considering, in the title essay, an earlier essay she wrote in college on the subject of literary vividness. “I want to travel back in time and help her.” She knows that nothing she “could have done could have saved me, but all the same I can’t stop wishing.” The only recourse available to her, as the book testifies, is to tell and to retell the stories, in all their various “versions (visions),” “not in order to remember…but in order not to entirely forget.”

As for what Ives needed saving from, the list is—for all of its heady trappings—familiar. Love, insomuch as it exacts its toll on a younger Ives, takes a beating in the book. “[M]y goal,” she writes in “Earliness, or Romance,” “is to convince you that it could be worth considering the notion that your idea of what is romantic, of what is sexy, compelling, might originate in emotional survival techniques you no longer recall acquiring.” Perhaps those techniques are not always maladaptive, but what is one to do at four-years-old when, say, one’s parent throws one’s cat against the wall? What emotional survival techniques does one learn, and how do these translate to grownup life? “Thus, in this account, do parents win for their children their future partners.” After a partner or two of this sort, one might reasonably conclude that “romance is not all there is and not the best thing possible.” That was one flavor of our innocence: we didn’t know what we didn’t know, but our avenues for finding it out were old-fashioned. The postlapsarian internet might have warned a young person, as through a series of Instagram slides, about the toxic traits one might encounter in a partner. It might have warned us about the kinds of harm people who harm animals inflict on other people. We had to find out the hard way.

In one of the collection’s most striking passages, Ives describes a visit she pays, at fifteen or sixteen, to a sexually adventurous friend she calls Albertine. Albertine is in the hospital because “the human papillomavirus caused either warts or precancerous lesions to form on her cervix,” and their surgical removal led to a lot of bleeding. Ives admits she doesn’t understand, staring at her pale friend in a hospital gown, “what has happened from a physiological point of view, and no one goes out of their way to enlighten [her].” This takes place sometime during the fall of 1995 or the spring 1996. At the time, I was a junior in high school. I had never heard of HPV, and even if I had, I would hardly have known how, much less why, to find out more. Maybe the library’s row of leather-bound encyclopedias contained an entry, but would I have needed to look in the “H” volume or the “P”? You know that slightly panicked feeling when you’re a long way from home, and you only sort of know where you are, and then your phone dies? Not too long ago, life was like that, but almost all the time.

If the idea in “Earliness, or Romance” is that we unwittingly absorb, as young people, the habits and pathologies that haunt us as adults, one’s formal education is often no less troubled than the sentimental one we received “when we could not survive on our own.” Teachers can do to our minds what parents do to our hearts. In the aforementioned abecedarian, the first of the pair of longer essays that conclude the book, Ives details, among many other things, her brief apprenticeship to—and long admiration of—the late literary critic Barbara Johnson, a former protégé of Paul de Man. Near the conclusion of “The End,” which deliberately does not conclude as such, Ives recounts an exchange with a philosopher friend. “Oh my Lucy,” the friend writes, after Ives admits that “I used to put myself in danger.” She means physical danger, yes, and gendered danger, but she means intellectual danger as well. “I think my friend is saying,” Ives imagines, “Hey, I’m sorry you got mixed up with complicated critics at such a young age.”

Is there an intellectual version of throwing a cat against the wall? If so, it may have been deconstruction or “high theory. The French invasion. Post-structuralist hijinks. Whatever you want to call it.” Ives isn’t, to be clear, making that particular moral equivalence, but the parallel still holds in that there may be intellectual survival techniques you develop at a young age, in response to how your elders engage with the world. As with your affective strategies, these ones, over time, may not serve you well either. You may find yourself, as a much older person, with your thinking in knots. The thing in which you invested your every ambition might be the very thing standing in your way of living a healthy life. “[O]n one hand,” she observes, “my love of language is what allowed me to survive several decades of mental instability and illness, and, on the other, my love of language seems to have delayed my recognition that I needed help.”

How many of us, I thought when reading those lines, could say the same thing? How many of us were hemmed in as people who have to live in the world—buying groceries, paying bills, raising children—by the intellectual methods we were taught? I remember one stinging critique I received in a graduate-level workshop. “There are no pronouns in these poems,” the other writer said of my work. Meaning: there are no people, not even you, the writer. Imagine my surprise when, in my late twenties—done with grad school and newly a parent—I had to learn how to be a person all over again.

In the collection’s final and longest essay, “The Three-Body Problem,” about the birth of Ives’s son, it is as though the fever of the previous four breaks. This is not to say that in childbirth and motherhood Ives finds some sort of salvation. Her thinking and way of being in the world are far too intricate and nuanced for such clichés. It is, instead, that she realizes she is “more like other people than I had ever, ever imagined I could viscerally feel I was”—and she’s grateful for this. And yet, though the body of her son has delivered her into her own body, into its common corporeality, the experience required for her “a particular consideration or thought work” that she has yet to resolve. In this way, where the other essays look back, the final essay looks forward. “For years, years that begin in 1999, I hold my breath,” Ives writes in “The End.” “Here I am, then,” she counters in the final essay, “in the endless after, talking to you.”

As James Webster suggests in his thoughtful review, there’s a certain facile criticism that can be leveled at the book, and kindred works, wherein the writer is essentially accused of being both a scatterbrain and a chatterbox. The writer, by virtue of their intellectual range, is cast as digressive or freely associating or, worse, superficial. Great works, this line of thinking holds, should synthesize. They should predigest a reader’s responses and redeliver them in the form, ideally, of a cohesive narrative. This is to argue, in effect, that a movie like Gladiator, fittingly released in the year 2000, is always preferable to a movie like Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love, released the same year. The notion, moreover, that a book like An Image is a product of “The Maggie Nelson Industrial Complex” (Webster playfully cites the term, though it is not his) is a-historical, among more biting things one might say about it. Writers have been playing with the forms Ives employs, and all of their associated permutations and paradigms, for at least a thousand years. The idea that Maggie Nelson invented or popularized the approach gives an important writer the wrong kind of credit.

An Image of My Name Enters America may not be an easy or straightforward book, but to dismiss it as a hodgepodge would be a lazy reaction. One born, perhaps, of an age when every movie is just a click away, and when an answer to every question you might ask (even if it isn’t the right one) lies in that device in your pocket, which—not coincidentally—is tracking your every move.

“There was something to this time,” Ives declares in “The End,” “the early post-millennium, the dawning of the popular internet, in that it nominally resembled a series of times…in which young men went out into the landscape to find themselves and test their minds and bodies against nature.” Except Ives wasn’t a young man, and the landscape in which she was finding herself was about to change forever. How does a person, especially (though not exclusively) when one isn’t a man, find oneself in a world going/gone astray/asunder? With one foot in the past, and the other in the present, a person can only feel pulled apart as the gap grows larger.

These days, those ambitious young men I once knew are now middle-aged. They have careers, mortgages, kids. One of them, the erstwhile Derridean, made a fortune in Silicon Valley. Each of us, I think, has let go some part of who those earlier times allowed us to believe we could be. On one hand, that’s just a part of growing up. But for us late Gen X-ers, that maturation was also shaped by tectonic shifts in the way we understand and interact with the world. It’s been bewildering in ways other generations aren’t historically positioned to perceive. Thankfully, for their benefit and ours, Ives has captured the feeling precisely.